Emerald Opulence and its Discontents: What I Would've Worn to the 2022 Met Gala

A brief history of arsenic green and the karmic consequences of democratized consumption

Like millions around the country, my roommate and I huddled around a laptop to watch the spectacle of the Met Gala, captivated by the waltz of the red carpet and avante-garde gowns worth more than our college tuition. “Ugh, that is so ugly,” my roommate sneers at Cara Delevigne’s Dior ensemble. Most will agree that the fun of the Met Gala lies in the commentary, indulging our impulse to praise or harshly criticize the lavish outfits online. Social media erupted after the event this year, with many questioning why no one seemed dressed for the theme. And while I have definitely engaged with the post-Gala discourse, I can’t seem to shake the idiom, “Those who can, do. Those who can’t, critique” from my head. So, in the spirit of that sentiment, I’d like to present what I would have worn to the Met Gala (had the invitation I was definitely sent not been tragically lost in the mail, of course), a glimmering Emerald gown which embodies the contradictions of America’s past and present.

Artwork by Wynona Bernasconi (the roommate)

This year’s Met Gala theme was “Gilded Glamor”, a nod to the period of rapid industrialization and cultural change following the American Civil War and ending at the turn of the century, known as the Gilded Age. Towards the end of the 19th century, the factory, mining, financial, and railway industries exploded seemingly overnight, and suddenly a new legion of elites were able to break into high society without the patrilineal inheritance of old money connections. Industrial production reduced prices for many goods which were previously unattainable for the middle class, particularly clothing and textiles, and an influx of Europeans migrated to the United States to work in its rapidly expanding industrial sector. At the time, some heralded the newfound economic mobility as a democratizing force, but as the Vanderbilts and Rockefellers amassed their fortunes, the working class suffered through the exploitation and abject poverty characteristic of unrestrained industry. Mark Twain coined the term Gilded Age in his lesser known 1873 novel The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today, which satirized the era of concentrated wealth, profound decadence, and serious social problems brushed over by a thin gold gilding.

19th century innovations like electric and steam powered looms made fabric easier and cheaper to produce than ever before, and the invention of synthetic dyes replaced the previous hues derived from mineral or animal material, which were often expensive and unpredictable. Synthetic dyes dramatically reduced production costs, and chemical synthetization allowed for seemingly infinite color permutations which could keep up with shifting consumer tastes. These innovations democratized textile consumption to some degree, with middle class Americans suddenly granted the privilege of purchasing new clothing regularly, but this democratization came at high costs. Pollution was rampant, and the chemicals used in textile factories contaminated the air, soil, and waterways surrounding them. But environmental contamination was not the only consequence of loose regulation, as consumers would soon discover.

In 1814 the Wilhelm Dye and White Lead company introduced the fashion world to the latest craze: Emerald Green. Color experts found it incredibly difficult to produce a long-lasting rich green color until a chemist at the London-based dye company produced the chemical compound known as copper arsenite by mixing copper with white arsenic. Yes, you heard that right: arsenic. This mixture produced a dazzling jewel tone with a remarkable eye-catching quality that sent ladies in America and Europe into a frenzy. The color was used so frequently in clothing, home furnishings, wallpaper, and even food that by the middle of the 19th century, Britain was said to have been “bathed in green”.

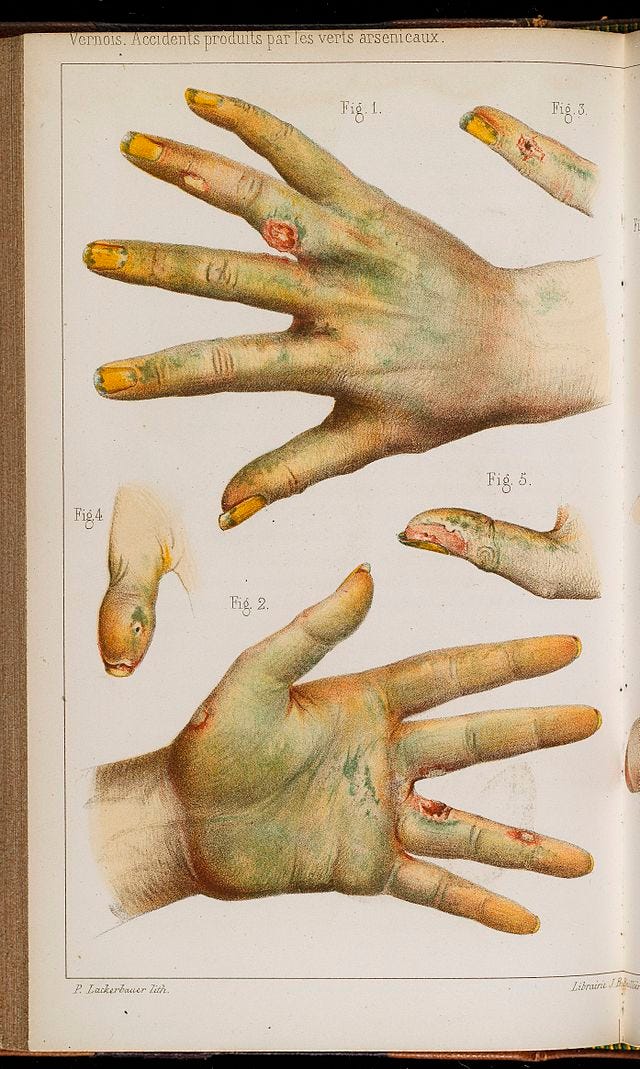

Quickly, some ladies noticed their new green gloves were giving them chronic sores on their fingertips. Parents reported children dying from sudden onslaughts of illness, waking in the night with horrible abominable pain and unable to draw their breath. Coroners would come to the family home to bring the bodies to the morgue, carrying the children away from their beloved bedrooms, which were recently redecorated with green wallpaper. Women would adorn their eyelids with emerald pigment and use the same pigment to cover the gruesome sores that developed. As people sweat throughout the day in their Emerald Green garments, arsenic dye leeched onto their skin. If a room plastered with the wallpaper were to get damp or humid, arsenic gas would seep into the air. Four to five grains of arsenic were enough to kill the average adult. The average Emerald gown contained nine-hundred grains of arsenic. But as with most dangerous consumer products, the workers producing them endured the most horrific consequences.

On November 20th, 1861 Matilda Scheurer, who worked in an artificial flower factory, came to her doctor with disturbing and mysterious symptoms. She was covered in sores and convulsing, she couldn’t stop vomiting green bile, the whites of her eyes turned green, and she told the doctor that everything she saw was painted emerald. In the hours leading up to her death, she was convulsing every couple minutes, her eyes, nose, and mouth producing an eerie green foam. Needless to say, the physician was shocked. As Sheurer prepared the fake flower stems each day, she dusted an Emerald Green powder over the leaves, a powder which was thin enough for her to inhale. Her and her coworkers’ hands would be covered in the substance as they ate their lunches, unaware that they were directly ingesting lethal amounts of arsenic dye. In French textile factories, workers called appreteurs d’étoffe would dye cloth with copper arsenite and stretch it out to dry over a wooden pallet covered with jagged nails. The nails would lacerate their hands, arms, and torsos, sending the poison directly to their bloodstream. In nearly every factory working with the synthetic dye, workers’ hands were wrapped in bloody bandages, their bodies covered in painful sores, and their lifespans rarely extending beyond a couple years after they began working there. Scheurer’s death was ruled an accidental poisoning.

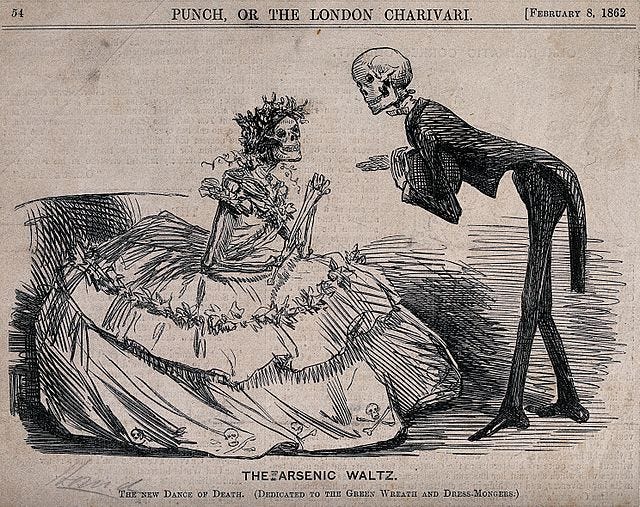

A women’s organization known as the Ladies’ Sanitary Association (LSA) took up Scheurer’s case, commissioning independent chemist Dr. A. W. Hoffman to investigate the toxin levels in her former workplace. He relayed his findings in a sensational article titled “The Dance of Death” upon discovering each floral headdress contained enough arsenic to kill twenty people. During this time period, arsenic was classified as an “irritant” poison, meaning it was known to cause skin lesions, but people believed if they weren’t going around licking their wallpaper or evening gowns, they were safe. Arsenic was a popular item in American and British households, frequently used in rat poison and medicines. Children could even buy it at their local pharmacies. As the government began recognizing the substance’s toxicity, they passed a couple pieces of legislation like the Control of Poisons Bill of 1851 and the Arsenic Act of 1868 which limited sales to individuals, but large-scale use in the industrial sector remained legal and relatively unregulated. While the LSA investigation broadened public awareness of the danger of Emerald Green clothing, its use was not banned until a hundred years after Scheurer’s death. Today, seamstresses still harbor superstitions about green garments, a relic of the color’s horrific gilded origins.

Amidst our current situation of mounting inflation and wealth inequality, some critics described this year’s Met Gala theme as “out of touch”. Some attendees, like Riz Ahmed, used the theme as an opportunity to highlight the exploitation of the era, but many interpreted “Gilded Glamour” by wearing glittering gowns that were as inoffensive as they were trite. At some level, I don’t even blame the designers or celebrities for shying away from an opulent tribute to the era. The day after the Met Gala, Twitter was ablaze with critiques about the lack of adherence to the theme, but can you imagine what it would have looked like if people had? Pure rage. Class warfare.

There’s an ongoing national conversation about how to reckon with America’s often unscrupulous history. The founding fathers were slaveowners, the Vanderbilt railroad fortune was built off the backs of exploited Chinese immigrants, and your favorite color actually mutilated millions of textile workers; nothing is safe. Yet we are called to conceive of history as a story of linear social progress, about Great Men who did Great Things, and a steady trend of increasing quality of life, but when we look into the lives of the workers who actualized these visions of development, the narrative rarely fits into an easy definition of “progress”. While we recognize that economic and social transformation often comes at great costs to folks who aren’t in power, we haven’t been able to kick the benevolent-progress lens of history because its narrative is so compelling. Beginning in our first social studies classes, we are immersed in a historical canon which seeks to present the hopeful face of development, in which all of our society’s past problems come to be remedied by the predictable, altruistic force of history. We hope that our current social issues will be naturally resolved as time moves forward, that things are always getting better without us having to solve our own problems. But as Twain’s initial coining noted, the central theme of the Gilded Age was the vast disparity between the economic prosperity of a few elites and the suffering endured by those who kept the wheels of industry churning. Often, examining life for the most disenfranchised groups in society gives us the most accurate picture of historical development, which is filled with contradictions such as the Gilded Age’s equalized purchasing power and simultaneous endangerment of the public. Increasing access to opulence often means new opportunities for the middle class to engage in the same exploitative consumption as the elites, and is often met with karmic consequences, such as Scheurer’s literal “seeing green”.

The Met Gala theme was rife with opportunity to illuminate issues of today which resemble the simultaneous decadence and degradation of the late 19th century, like fast fashion, climate change, industrial pollution, classism, wealth inequality, etc. We have more access to “luxury” goods than ever before, and we are implored to transcend the problems of our predecessors – aging and disease and poverty – by cultivating elaborate skin care or supplement routines. While we may not wear dresses dyed with poison anymore, almost all the commodities we consume contain known and unregulated carcinogens, and when the consequences of limited regulation rear their ugly head, we are left to set up a GoFundMe page while the titans of industry who sell them to us waltz across the red carpet. Even the celebrities in attendance this year represent the democratization of fame and fashion, with breakout internet starlets walking alongside some of the most respected entertainers in the business, each conspicuously performing the lavish lifestyle of elite society. Designers’ apprehension to tap into an honest examination of the contradictions and controversy in the theme feels spineless, but even worse, uninspired in a way that feels willfully ignorant to their position.